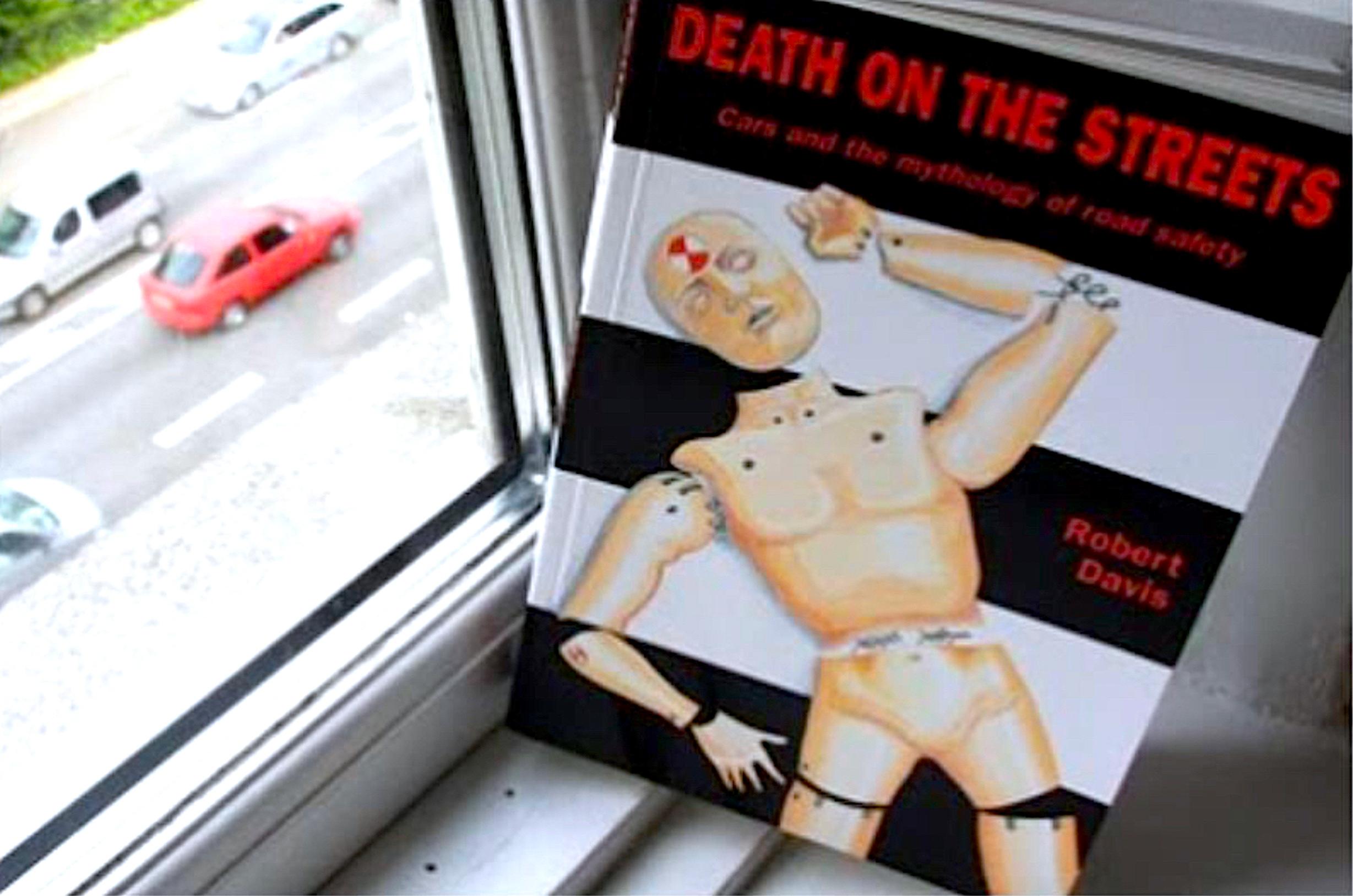

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Road Danger Reduction Forum (RDRF). Tempus fugit indeed! It all started with a conference organised by Leeds City Council to address issues raised in my book Death on the Streets: Cars and the mythology of road safety.

Amid the discussion and debate, the RDRF came into being, comprising a group of experienced Road Safety Officers (RSOs), transport planners and highway engineers.

A key issue covered at the conference was how to measure success. This is not as straightforward as it might seem. While reduced reported Road Traffic Collision (RTC) casualties may appear to indicate success, this is not necessarily the case.

For instance, what happens if ‘success’ is due to more benign road users walking and cycling have moved from the highway environment – often precisely because that environment has become more hazardous? For us it was and is crucial to oppose this as indicating progress, and to use better metrics of success than ‘casualty reduction’.

Secondly, we wanted safety on the roads to be considered from the perspective of health and safety regimes elsewhere – where the focus is on where danger comes from, in this case from the (mis)use of motor vehicles.

Thirdly, we wanted recognition of how human beings constantly adapt to their perceptions of danger (risk compensation or behavioural adaptation). Sometimes this can be beneficial – increased vigilance from road users in more congested conditions, known about since the work of Reuben Smeed 60 years ago, and how increased cycling brings about ‘Safety in Numbers’.

We also looked at the adverse impact of more crashworthy vehicles (seat belts etc) on the safety of people outside cars. Above all, we explored whether so-called success is because people were not using (or allowing children to use) benign modes because of road danger.

Finally, we noted that regulation of safety on the road has been under the governance of Government Departments or Ministries supporting increased motorisation. This is at odds with what is needed; a shift away from private motor vehicle use, whether because of the health benefits of active travel, avoidance of local environmental damage from road building or the requirements of decarbonisation.

Two new phrases have emerged in recent times: Vision Zero and Safe Systems, both of which will be familiar to road transport practitioners. But, in reality, have these buzzwords made any difference? While a number of partnerships are making the right noises in the name of Vision Zero, we continue to witness the pain and loss linked to serious or fatal casualties. Talk of Vision Zero has not led to any significant increase in road danger reduction – and as we know, reductions in casualties (towards zero) can accompany increases, or at least no decrease, in road danger.

Safe Systems, meanwhile, push the idea that interventions must be based on the fact that human beings are fallible and prone to error. Again, I’m not sure that this has actually led to successful interventions in cutting road danger in the UK. What is interesting is that accommodating driver error (through engineering highway and vehicle environments) has been a feature of official ‘road safety’ practice for decades. It would be about time if pedestrian and cyclist mistakes are similarly accommodated.

What about the central point of our approach? It’s good to see an example like Transport for London’s current Cycling Action Plan (p.42) include a chapter headed, “Tackling the sources of road danger”, and some police services referring to “harm reduction”. But the critical point is what local authorities and safety partnerships actually do, and I would be wary of claiming much progress.

One key step forward has been the acknowledgement of a “hierarchy of danger” in “The Hierarchy of Road Users” (Rule H1) in the revised Highway Code. What had seemed like an obvious moral obligation has now been clarified, although inadequate publicity may mean that the relevant responsibilities are not known (let alone accepted) by many motorists.

Awareness of what is termed as ‘risk compensatory behaviour’ has, at least, spread from a few academic researchers to the wider transport practitioner community. I believe that engineers and designers have incorporated such insights into (at least some of) their thinking, whether it be in debate about ‘Safety in Numbers’ or recognition of the potential benefits of removing pedestrian guard railing.

So, have we managed to get these viewpoints onto the official transport agenda? The phrase ‘road danger reduction’ is used by a number of local authorities and the organisations representing road crash victims and walking and cycling – at least in name.

On the key issue of metrics we now have what is sometimes referred to as a ‘who/what kills whom’ metric – highlighting the third party involved in RTCs rather than just the victim: https://rdrf.org.uk/2019/03/12/who-kills-whom-and-the-measurement-of-danger/

Following collaboration with the Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety (PACTS), this is now published in official statistics as Charts 4 – 6 in: Reported Road Casualties: Road user risk 2021

So, that’s a step forward. However, former transport minister Norman Baker stated, “…(for) the rate per 100,000 of the population, in terms of cycle deaths, …we actually come above the Netherlands. We’ve got a better record on that”.

But this overlooks the fact that there is much higher use of bicycles in the Netherlands. In reality, we see a much lower casualty rate (per journey or distance travelled) in the Netherlands compared with the UK. Until, at least, such a risk measure is given primacy over casualties per head of population for active travel we’ll be stuck in the past.

And for those spellbound by stats, we can take the ‘Beyond Zero’ approach of incorporating life years lost from: inactive transport; noxious emissions, greenhouse gas emissions; and spending on road building rather than health care into calculations as well as RTC deaths and injuries.

As for traffic reduction and modal shift… in 1997 we had this claim from the then secretary of state for the environment, transport and the regions John Prescott: “I will have failed if in five years’ time there are not many more people using public transport and far fewer journeys by car.”

And what of Cycling England’s target of quadrupling cycling by 2012? So, there will indeed be scepticism of the current targets for increased active travel mode shares in urban areas.

Nevertheless, I regard the Johnson administration’s publication of Gear Change and LTN 1/20 as heralding new possibilities. The problem, of course, is that any push in the sustainable direction can be negated by the continuing commitment to road building for more motor vehicles.

In summary, there have indeed been big moves forward at least on the ideas front. Positive voices are heard from police officers willing to enforce close passing of cyclists and 20 mph areas. The advent of social media and technologies unavailable 30 years ago have brought third party reporting into consideration.

And it is in the ‘battle of ideas’ around LTNs and elsewhere where we can raise the fundamental issues of the safety of all road users. The basic moral issue of whether some road users should be able to endanger, hurt or kill others has, in I would argue, been brought forward by our Road Danger Reduction movement. It is part of cultural change of seeing the source of road danger as problematic rather than its victims.

To conclude, when confronting the opponents of road space reallocation (and other measures to reduce car dependency) consider the words of then prime minister Boris Johnson in the first annual report of Gear Change: “I support councils, of all parties, which are trying to promote cycling and bus use. And, if you are going to oppose these schemes, you must tell us what your alternative is. Because trying to squeeze more cars…on the same roads and hoping for the best is not going to work”.

So, do you have an alternative? Or do you want to be less responsible than Boris Johnson if you don’t?

Dr Robert Davis is chair of the Road Danger Reduction Forum

This article is dedicated to the memory of Mike Baugh, who died recently. Mike was a co-founder of the RDRF in 1993. He worked as a Road Safety Officer for Avon, Bath and North East Somerset, and Bristol City Councils

TransportXtra is part of Landor LINKS

© 2025 TransportXtra | Landor LINKS Ltd | All Rights Reserved

Subscriptions, Magazines & Online Access Enquires

[Frequently Asked Questions]

Email: subs.ltt@landor.co.uk | Tel: +44 (0) 20 7091 7959

Shop & Accounts Enquires

Email: accounts@landor.co.uk | Tel: +44 (0) 20 7091 7855

Advertising Sales & Recruitment Enquires

Email: daniel@landor.co.uk | Tel: +44 (0) 20 7091 7861

Events & Conference Enquires

Email: conferences@landor.co.uk | Tel: +44 (0) 20 7091 7865

Press Releases & Editorial Enquires

Email: info@transportxtra.com | Tel: +44 (0) 20 7091 7875

Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | Advertise

Web design london by Brainiac Media 2020